What was the ancient Greek world that the Romans encountered?

by George Sharpley | Sep 26, 2020

Greece as we see it on a map today is a smallish country with a number of small islands, and no part more than forty miles from the sea. The land is divided by mountains, separating the ancient cities (poleis), which were seldom capable of laying aside their squabbles (on the plus side, Greeks were good arguers) or achieving unity unless coerced by an external aggressor (Macedonians, Romans), or the threat of one (Persians). If Greeks rarely came together as a single unit, they nonetheless shared a cultural identity by their recognition of what they were not: barbaroi (barbarians).

The reality of the ancient Greek world is a much more elusive concept depending on what, when, and who. A seminal centre of Greek culture wasn’t in Greece at all, but on the other side of the Aegean – Ionia. Homer was said to have lived there, and so too those Greeks who first subjected established traditions and accepted beliefs to scientific and philosophical scrutiny. The first lyric poets we know of (7th/6th centuries BC) lived here or in islands close by, and to the south was the city of Halicarnassus, home to Herodotus, first of the Greek historians.

For ‘Classical’ Greece we zoom in to Athens in the 5th-century BC, prosperous and powerful after the Persian Wars. This city, population-wise about the same as Coventry, gave us the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes, the debates of Socrates, Plato, the prestigious Parthenon, their democracy, political debate, other writers such as the next great historian, Thucydides, and the most lavishly beautiful art. Much of what we think of as Classical Greece was in reality the output of Athens. What this city didn’t produce from its own citizens it supported or commissioned from others. Herodotus, for instance, after he fled his homeland.

From Athens we pan out to a much broader Greek world, which came into being long before and lasted long after the Classical period. There are traces of this culture scattered all around the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. What do the cities of Nice, Marseille, Naples and Syracuse have in common? They were all Greek colonies. As early as the 8th century BC enterprising missions took to the seas, motivated perhaps by land shortage or political oppression, or opportunity for trade, or simply a sense of adventure. Different Greek cities were behind the moves, and most new colonies kept ties with their homelands (metropoleis). These colonies sprang up close to the sea, ‘like frogs around a pond,’ said Plato. Some established new colonies of their own. They retained their metropolitan characteristics, of politics, culture, and inter-city squabbles.

Sicily and southern Italy were particularly popular destinations. Many colonies were settled there from different metropoleis, which the Romans called Magna Graecia. For centuries the dominant language in southern Italy and Sicily, near the coast at least, was Greek. These cities would have been for most Romans and other Italians their primary contact with the Greek world. They had assemblies, theatres and temples. They had their own poets, pot-painters, sculptors, philosophers and playwrights, and all the advances in science. Some had democracies, though these were always vulnerable to switches of loyalty and powerful aggressors. No change there from their metropoleis, some of which never had a democracy in the first place.

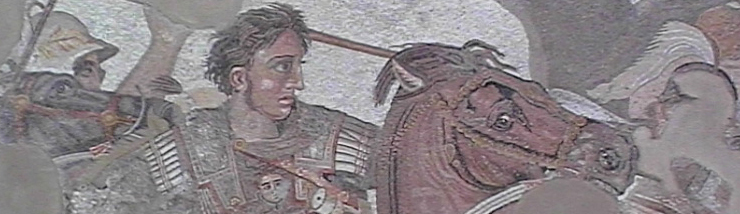

A further broadening of the Greek world happened in the 4th century BC, with an impact across the near east and Egypt: the legacy of Alexander the Great’s conquests, which became known as the ‘Hellenistic’ world. Alexander’s successes were phenomenal. While it is true that to defeat the existing imperial power, the Persian dynasty of Achaemenids, would make the subduing of all their subjects and vassal states easier, what he achieved is nonetheless extraordinary: not least how far he travelled in the thirteen years of his reign. He died in 323 BC, after which his empire was divided between leading Macedonians. The new Hellenistic spirit thrived for centuries throughout the region, even in its remoter corners. ‘Barbarians’ became avid fans of Greek plays. In 53 BC Crassus’ Roman army was crushed by Parthians from the east, and news of this was delivered to the Parthian king while he was watching the Bacchae by Euripides. In Egypt, the Ptolemies held power for almost 300 years, culminating in the reign of Cleopatra. It is no coincidence she shared the same name as Alexander’s sister.

During this Hellenistic era (3rd and 2nd centuries BC) the focus of the Greek world moved again when Alexandria, a city which Alexander founded in 331 BC on the coast of Egypt, displaced Athens as the cultural centre of the Mediterranean. Alexandria had a magnificent library, full of scholars and poets, whose studied homage to previous centuries of Classical literature still managed to produce a fresh take on those models.

* * * * *

It was this Hellenistic world that Rome encountered as it grew into a Mediterranean superpower. Romans had long been buying Greek products in Greek pots and sharing Greek stories and Greek gods. Now, in the 3rd century BC, stories are written in Latin for the first time. The naval victory over Carthage in the First Punic War had liberated traders to sail to Alexandria and there source the material needed by a literate society: papyrus.

Roman storytellers and poets absorbed the Hellenistic literary canon, retelling myths of ancient Greece. Some they adapt to the mythology or history of their own land, but many are Greek. Much of the Greek content of these stories had been ingrained in the Italian tradition of oral storytelling long before, from travelling Greeks from Magna Graecia and elsewhere. The earliest surviving Latin plays written in the 3rd century show how familiar audiences were with Greek tales.

So in broad outline I see two strands of influence on Rome. One, older, orally passed on, much of it below our radar, from Magna Graecia and beyond; the other, the Hellenistic world of Alexandria, and with it the literature of Classical Greece. Rome’s acquisition of Greek culture was accelerated by their military conquest in the 2nd century BC. At that point, thousands of works of art were carted back to Rome, and with them slaves who would educate the sons of the wealthy. As time went on, anyone with half a sense of taste and twice as much money bought sculptures and other valuables and ferried them back to Italy.

The fusion of Classical and Hellenistic strains in Roman literature reaches maturity by the time of the poet Ovid (43BC – c.AD17). His Metamorphoses has echoes of both, and offers the most fruitful single source of ancient myths. It is a triumph of storytelling, in one swoop confirming that Greek stories were familiar to Italians too. However, the majority of his tales are not set in Italy, or even in Greece, but in the near east.

Recent Comments